|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Breeding program management |

|

|

|

|

Intellectual Property Rights and Germplasm Exchange: the new rules |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction

Breeding improved varieties relies on access to suitable parental germplasm. However, gaining access to suitable parental germplasm is becoming increasingly politicized and legally controlled, subject to developing international agreements as well as to national legislation.

These questions are difficult issues. Resolution of the issues is a matter of policy and human rights more than of science. Yet we must understand the issues and comply with the associated policy and law, so that we can achieve our objective of poverty alleviation without contravening human rights.

|

|

|

|

|

Changing concepts and international agreements

Modern practice in all commercial areas (buying and selling some kind of property – a DVD, for example) is based on separating TANGIBLE PROPERTY from INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY. The tangible property is the physical thing that we can touch: the DVD itself. The intellectual property is the knowledge and know-how required develop and find out how to produce and market a product – in our example, that could be everything involved in producing a film on the DVD.

This separation of tangible and physical property is necessary to support the heavy investment that modern industries make in producing an affordable product. A film company might invest US$100million in developing a film, and release it on a DVD worth US$1. The company somehow needs to recoup its US$100million investment, by selling the DVDs at a price that reflects its investment in making the film on top of the physical cost of the DVD. Yet if anyone else copies that DVD for commercial sale without having invested in making the film, they could obviously easily outcompete the original company.

The solution in trading almost any product is to sell the tangible property but not the associated IP. If you buy a DVD, it is illegal to make and sell a copy. If you buy a packet of rice in the supermarket, you buy the rice for the purpose it is sold – i.e. to cook a meal; but you do not buy the right to use the logo on the packaging. In many countries, when a farmer buys a sack of seeds from a seed company, those seeds can be used to produce and sell a crop but cannot be retained for further breeding.

The separation of tangible and intellectual property is a major change from traditional practices. Traditionally, there was no distinction between the tangible and intellectual property components of a product that was bought, bartered or exchanged. The owner of the product was allowed to do anything with it.

Modern concept of ownership: separation of tangible and intellectual property

Use of plant genetic resources has lagged behind the rest of the industry. Until recently, when plant breeders obtained a sample of crop germplasm, they expected to be free to do anything they like with it. Doubts about the acceptability of this doing started to develop during the 1970’s and 1980’s. There was a transition period when the plant breeding sector apparently expected to be able to protect the IP on its improved varieties while having free access to farmers’ germplasm.

Doubts culminated in the ground-breaking CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY (CBD) in 1993. This was a key moment in history, redefining internationally accepted concepts relating to the conservation and exploitation of biodiversity. The CBD is now almost universally accepted: 193 sovereign nations are Party to the CBD, leaving only 4 exceptions: USA, Vatican, Andorra, and South Sudan.

Parties to ITPGRFA and CBD

The CBD has 3 key components:

Although the CBD encouraged germplasm exchange, at the same time it raised the required level of negotiation and authorization from the individual scientist to the government. This had a very negative effect on germplasm exchange.

The INTERNATIONAL TREATY ON PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE (ITPGRFA) was negotiated as a direct response to the CBD, to facilitate access to crop genetic resources in harmony with the CBD through an efficient mutually agreed multilateral system of access and benefit sharing.

The ITPGRFA has 2 key components:

Thus the Treaty directly addresses concerns that lead to current problems.

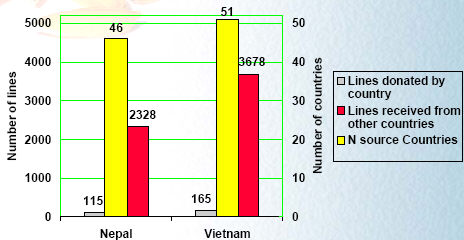

The benefits of exchange: A country gains much more than it contributes.

|

|

|

|

|

Click here to see a detailed slide show on the procedure of germplasm exchange with IRRI.

|

|

Let's conclude |

|

Summary

|

|

|

|

|

IRRI and rice genetic resources:

|

|

Next lesson |

|

Up next is a quiz to check your understanding of module 3. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.gif)